By Mary Scheetz, Former Assistant Superintendent, Waters Foundation and Peter Senge, Sloan School of Management MIT and SoL (Society of Organizational Learning)

Systemic change is deeply personal. This simple but paradoxical idea is perhaps the key reason most efforts at systems transformation are so disappointing. Something in the very word “system” or “systemic” consistently leads us astray – seeking some magical change “out there” when the most intransigent aspects of the “out there” are inseparable from our habits of thought and action “in here.”

Nowhere is this misconception more tragic than in efforts to address the extraordinary inequity in America’s schools. The many tangible dimensions of inequity in school resources like class size, teacher preparation, curricular relevance and student opportunity are inseparable from deep mental models about the capabilities and potential of students. Since pioneering research 80 years ago by Thomas Merton on the “Pygmalion Effect,” we have known that teacher assumptions about student capability directly impacts student performance. This basic “self-fulfilling prophecy” shapes a reinforcing feedback loop that operates with entrenched societal norms and biases to dampen student achievement. This, obviously, was the point of the famous George Bernard Shaw play (later restaged as the musical My Fair Lady) from which Merton drew the evocative metaphor for his research findings.

We have had the privilege to work with many committed leaders who have managed to “push the needle” on these profound issues. The aim of this article is to share what we have learned from them.

But what strategies and principles does understanding the “inner” nature of inequity help us identify? How does it help those determined to reverse growing inequity in America’s schools succeed in doing so? How does it help us understand which strategies that, while well-intentioned and sincere, are destined to be low leverage?

We have had the privilege to work with many committed leaders who have managed to “push the needle” on these profound issues. The aim of this article is to share what we have learned from them.

Some Basics Regarding Mental Models

We do not “have” mental models; we “are” our mental models. None of us sees an external reality as it is. As is said in the philosophy of language, “We do not describe the world we see; we see what we know how to describe.” This is not a tragic flaw. It is what it means to be human. None of us can see our own biases. The more tragic problem, especially because it is avoidable, is that few of us operate in work environments that foster the trust and reflection that can allow us to see the shortcomings in our perceptions and how we operate. The consequence is that our inescapable biases go unseen and become subtly reinforced. For most educators in most schools and systems, no embedded processes exist to help people cultivate a vision of what is possible for all kids, continually reflect on their own limitations in realizing that vision, and to help those who do not share this vision to move on to other work.

Once we recognize this deep challenge, we realize that most efforts to address these inner realities that shape inequity of opportunity will continue to disappoint — until our approach itself shifts. Short professional development (PD) workshops can sensitize people to issues, but shifting deeply established habits of thought and action require time and an environment that balances objective observation and ongoing reflection. Creating such an environment represents a significant investment of time and resources to incorporate “learning infrastructures” into the daily routines of teachers and administrators alike.

Mental Models for Making and Sustaining Progress

When we have seen this shift achieved to some degree, it has been under the following conditions and guided by the following mental models. We don’t know if each of these is needed equally, or if all need to be in place. Every situation is unique, and effective change strategies invariably take this uniqueness into account. There is no “one size fits all” approach to systemic change. Still, we have found each of these ideas to be important.

The leader must be a zealot for equity who sees the big picture of challenges, but recognizes the opportunities to be a change agent.

1. Champions at the district, school and classroom levels who are zealous about equity.

“If it’s to be, it’s up to me,” as the saying goes. The leader must be a zealot for equity who sees the big picture of challenges, but recognizes the opportunities to be a change agent. This includes modeling a deep-seated belief in the magnificent potential of each and every child. The message from those in visible leadership positions that all students are to be fully served must be clear and consistent. Developing equity-based structures within schools and districts requires understanding the need to re-examine current systems of teaching, achievement, and discipline and confronting all potential inequities.

A superintendent in the St. Louis area exemplified this mental model. With her unwavering vision and her willingness to take a stance about the education that all students deserve, she facilitated significant improvement in student engagement and achievement as well as parent and community partnerships. She confidently led by example while inspiring others to embrace and facilitate change in a setting that had long embraced the status quo. For her, this was a natural outgrowth of what mattered to her. She did not see herself self-consciously as “the leader” of the process, but rather as one more person who needed to take a stand and continually examine her own shortcomings. In doing so, she became a model for many others to do likewise. Over time, this led to many shifts in how things worked in the school system, such as structures for ongoing training, coaching and peer collaboration to support culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy in an academic atmosphere of rigor, relevance and engagement for all students, regardless of background or past success.

2. Equity-based leaders are capacity builders.

Trusting that people can learn and change is essential. Again and again, we have seen that, in spite of lacking initial knowledge or skills, educators can develop the capacity to deliver culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy.

In Milwaukee, district leaders are facilitating a long-term capacity-building initiative, working in partnership with principals of schools targeted for improvement. Together, these leaders have invested in a long-term professional development process focused on meaningful instruction that engages all students in critical thinking and problem-solving that utilizes systems thinking strategies coupled with culturally responsive pedagogy. Six months into the process, we see significant achievement and discipline improvements are evident. The project is expanding to include parents and community members at the schools involved. Soon, a second cohort of district leaders and additional schools will become engaged.

The process of capacity building must be accompanied by a systematic approach to accountability for implementation and improvement that recognizes the tendency to adopt quick “fixes that backfire” inherent in the highly politicized, complex system of education. For example, it is common to attempt to intervene through short-term professional development or other “check the box” programmatic interventions. The tragedy of short-term PD arises from the unintended side effects: namely, that it reinforces a belief that there exist simplistic changes that are possible without examining difficult-to-see limiting beliefs and habitual behaviors. By contrast, when there are clear accountabilities, a principal, for example, can establish longer term interventions with clear indicators of progress that can be used for ongoing improvement and which can make visible persistent gaps that remain between intentions and outcomes.

“At some point, it’s not really about getting it or not getting it,” observed the assistant superintendent. “It is unacceptable to be culturally nonresponsive. The question is really how will we hold everyone accountable for improving how we serve ALL students?”

For example, in a Midwest, urban school district serving a high-poverty student population of more than 50 percent African American and Latino students that had been working on culturally responsive pedagogy for three years, a high school principal felt that “some staff members still don’t get it.” The assistant superintendent worked with the principal to implement instructional evaluation and feedback that increasingly included accountability for cultural relevance and responsiveness. Eventually, the teachers who “did not get it” realized that this really was their job, and those who were unwilling to change saw that their job performance was no longer acceptable. “At some point, it’s not really about getting it or not getting it,” observed the assistant superintendent. “It is unacceptable to be culturally nonresponsive. The question is really how will we hold everyone accountable for improving how we serve ALL students?” This relentlessness eventually helped that school and the larger district increase student and parent engagement and significantly improve academic performance. Today, it is sustaining full accreditation, while other districts with similar demographics are struggling to do the same.

3. Beware the tendency to shift the burden from true capacity building to programmatic interventions.

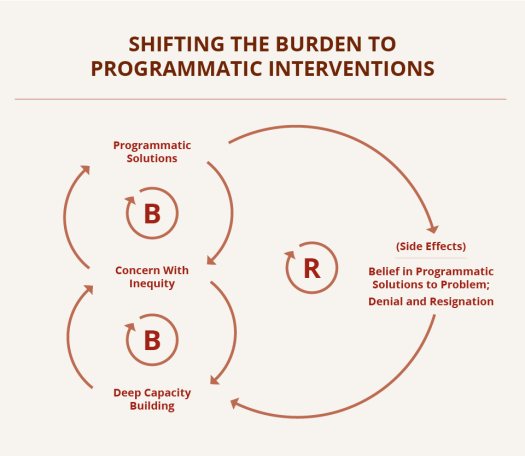

Adoption of a checklist of programs to address inadequacies can also shift attention away from the deeper changes needed — namely, developing of awareness, understanding and sensitivity to the ways in which we underserve many students. When not recognized, an archetypal “shifting the burden” dynamic subtly reinforces the tendency toward the programmatic and away from the developmental. This happens because as resources are directed toward implementing the programmatic solutions, concern for the urgency of inequity can decline as people feel they have addressed the issue, further shifting attention from deeper capacity building, as illustrated in the figure below.

In reading the figure, start with tracing around the “figure 8” on the left-hand side, starting with concern for inequity: As concern increases, programmatic solutions are implemented and concern decreases (the upper “balancing” loop); with diminishing concern, there is less emphasis on deep capacity building, which means that deeper causes of the problems are unaddressed and consequently symptoms of the problem and concern eventually return (lower balancing loop). Over time, this leads often to still more resources invested in new programmatic solutions, such as anti-violence interventions. The two balancing loops make the “figure 8” interact to create a vicious cycle, and the system “shifts the burden” toward depending more and more on low-leverage programmatic solutions. Over time, increasing dependence on low-leverage programmatic solutions lead to further side-effects, like denial and a belief that nothing can be done, which further undermine fundamental solutions.

The consequence of these shifting-the-burden forces is that practical know-how never develops regarding how to support true capacity building. But, this is not inevitable. Our experience shows that these insidious shifting-the-burden dynamics can be averted through four core elements that can eventually modify habitual beliefs and behaviors by building capacity:

- Make initial trainings

- Establish effective coaching for all — administrators and teachers alike.

- Build strong peer networks, which eventually supplant formal coaches.

- Create clear, effective accountability structures that track the impact of capacity building on the well-being of students.

There is an important role for meaningful introductory professional development, but only in concert with an integrated capacity building strategy. Reflective trainings move beyond PowerPoint presentations to invite participants to reflect on their own experiences of exclusion. Being on the receiving end of bias — be it gender-, ethnic- or profession-based — is an almost universal experience. This becomes a starting point for appreciating emotionally what many of our students are up against and for understanding further how we all subtly contribute to institutionally embedded bias.

When done well, this sort of initial awakening can then lead to greater openness to seeing how each of us can learn, especially when combined with ways to connect this to our daily work — such as through good coaching. Coaches attuned to embedded inequity can help teachers translate general concerns into better classroom practices that benefit all students. In the context of classrooms that effectively develop student engagement in and responsibility for their own learning, students increasingly voice their own learning needs. With good support, teachers can understand and address impediments to each student’s progress and gradually foster wholly new levels of engagement in their classrooms. Research shows that “by seeking to break down boundaries between teacher and teacher, teacher and student, student and the learning process, we will learn what students want and need. As a result, more and more teachers may go to bed at night remembering the images of wonder, enthusiasm and perseverance on the faces of their students.”[1]

Coaching is especially powerful when it helps develop peer networks where more and more of the “coaching” becomes embedded in peer-to-peer help. In the long run, no intervention is more resilient than robust peer networks that embody a cultural norm of continual and mutual learning. For example, in a large California school district with an ethnically diverse student population, including 27 percent English learners, peer networks involving more than 100 administrators from both the district and school levels, and including both instructional and non-instructional departments, have been established. Within these networks, small, purposeful learning community groups attend training together, followed by peer coaching sessions where they share strategies to improve how they operate within and between work groups. The focus of this multi-year professional development process is aimed at increasing the capacity of all to work in concert to become a district characterized by equitable and effective practices. As reported by one participant, “knowing that I can be honest about my challenges but that I can work with my colleagues as partners to meet those challenges has given me new courage and energy.”

As argued above, robust capacity building strategies require transparent management practices that create meaningful accountability structures based in connecting adult personal development and student outcomes. That said, there are several traps in developing effective accountability structures. First, it is common today that boards and external stakeholders force accountability structures on schools. Like any management system, the most effective accountability structures will be co-designed and accepted as useful by those to be managed, not imposed by those removed from the actual processes we are seeking to improve. Second, there are no perfect measures for tracking student well-being. While academic performance matters, it is often a lagging indicator. Before test scores and other summative, quantitative measures improve, principals, instructional coaches and teachers need indicators of improvements in process. Many of these will be informal and non-quantitative — for example, an increasing sense of efficacy (e.g., confidence in one’s ability to learn) can be a useful indicator of progress for a formerly disengaged student, well in advance of demonstrated academic achievement. Likewise, school and district climate audits can include measures that indicate the degree to which students feel valued, respected, encouraged, challenged and supported. Often, these audits also reveal the reasons why students are disengaged, absent and tending to drop out.

Like many, we have found that effective accountability systems blend qualitative and quantitative measures. “As with all policy changes, governments need to be able to measure success in improving equity, performance and school dropout rates. Numerical targets can be useful tools by articulating policy in terms of what is to be achieved rather than in terms of formal processes. A number of countries have adopted targets for equity in education. Numerical targets for reducing the number of school-leavers with poor basic skills and the number of early school dropouts are particularly useful.”[2] While we agree with this view, what it misses is the danger of relying too strongly on numerical targets. In the absence of meaningful qualitative indicators that committed leaders within the system can use to gauge progress, focusing exclusively on numerical targets can lead to countless ways to “game the system” to, as one savvy executive once explained to us, “look better without actually being better.”

4. The long-term consequences of institutionalized and socialized racism must be understood.

Continuous messages of being “less than” and seldom seeing images or hearing examples of hope and possibility take a toll on students and their families. The effects are much like the widely recognized impact of bullying. While the messages are often subtle (and sometimes not so subtle), the results are significant. The cumulative effects are exacerbated when we do not structure schools to address the inequitable distribution of advantages and opportunities experienced by students and generations of their families outside of school. We cannot expect students to engage in learning in a system that mirrors the racial and ethnic bias that they experience on a daily basis. This is not just about more money and better physical facilities; it is about programs, practices and policies that reflect explicit efforts to ensure learning and opportunities that are meaningful and engaging to all students, regardless of their race or ethnicity. Understanding the impact of institutionalized racism on student behavior, motivation and willingness to take risks can help educators be less judgmental and to employ innovative techniques to reach all students.

For example, one principal with a long history at Native American reservation schools and in other high-poverty settings, took over a “turnaround” school, where all the teachers and administrators had been fired. Given her background, she appreciated what this meant to the students and formed one overarching goal for the year.

Think how these kids felt. All their lives they have been on the outside looking in and now all their teachers have been fired. They felt more like losers than they ever had, if that was possible. Early in the year, one of the boys told me, ‘Mrs. Q…, there are ghosts in this building.’ My goal for the first year was simple: I wanted these kids to feel good about themselves, to feel like they had a future.

The school year ended with a talent show. The principal took this event as the bellwether for the year’s progress. “Middle school talent shows can be pretty rocky. Kids make mistakes. I have heard kids get laughed at, even booed. So, I was more than a little nervous when it started. When I saw that all the kids did was cheer, even when something went wrong, I knew we had turned a corner.” Educators like this understand the long journey to self-respect for students who have grown up in institutionalized racism and focus on the real indicators of building the social capital for change.

A particularly insidious dimension of institutionalized racism is white privilege, privileges taken for granted by some but not available to others. “When Americans talk about race and racism,” says University of California Berkeley, Law Professor john a. powell, “we almost always talk about African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos, sometimes Asian Americans, but we rarely talk about white people, the privilege of being the ‘generic’ category, which is a result of culture and power.”[3] We do not see the water in which we swim. This is true for all people, but when the water in which some have the privilege to swim consistently provides power, status and opportunity, there are strong forces to preserve the blindness. The key is to make the water visible through processes like courageous dialogue. Through a focus on mutual understanding, assumptions can be surfaced, in addition to addressing systemic and institutional bias, interpersonal bias can be identified and action can be taken in consideration of all perspectives, rather than solely those of the dominant culture.

The processes of self-reinforcing blindness are subtle and pervasive, but can be revealed by pausing whenever we see someone from a different background react in a way that seems odd or makes us uncomfortable. For example, it is an understandable reaction to criticize, if even completely internally, a member of a “minority” community complaining about something they see as unfair. “They could just ignore that if they wanted to, rather than just complaining,” we say quietly to ourselves. But we fail to notice that in this very thought we have constructed a “we and they” world in which we are projecting how we would feel when faced with a situation that, in fact, we never have had to face. This happened recently for one of us when an African American colleague was complaining about how she had to teach her kids “to never, not be on their guard.” By asking myself honestly, “When has this exact circumstance the person is describing ever happened to me? When have I felt that it was necessary for their safety to tell my kids never not to be on their guard because of their skin color?” The answer is never. In that moment of reflection, something that had been invisible became visible, and one small facet of the taken-for-granted nature of white privilege became evident.

Another archetypal pattern comes into play around white privilege that, once understood, can help people see what is difficult to see. “Success to the Successful” operates in any situation where there is a perceived scarcity of resources and resources are allocated in favor of those perceived to be successful. This can happen between departments within an organization, between different organizations (such as different schools), or between individuals. What results is a self-reinforcing drift where “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” But what makes a success-to-the successful structure especially insidious is when it remains invisible, and the reinforcing dynamics are masked by mental models that justify the inequity of opportunity as a natural or inevitable arrangement — as occurs with white privilege or the allocation of resources in some school systems.

In recent years, many school districts have instituted multicultural education programs. But to be effective, nuanced understandings of privilege need to infuse the related training and coaching. In our judgment, multicultural education is incomplete if it does not truly challenge the roots of structural racism and racial oppression, starting with the matter of white privilege. Addressing this topic through sustained and honest conversation leads to new perspectives and related action. One leader described her developing awareness and understanding of white privilege as “an awakening that is revealing the bias in many of my previous decisions and actions.”

Conclusion

If we are to reconstruct our educational systems to ensure equity for all, systems thinking is an essential skill, and the habits of systems thinking must guide our actions. This starts with understanding the power of mental models and looking for archetypal patterns like “fixes that fail,” “shifting the burden” and “success to the successful.” Systems thinking grows with sincere effort to reflect on the larger systems at play behind the behavior of individuals or particular groups. It is a defining feature of non-systemic thinking to over attribute outcomes to individual actions. While individual actions may be important, systems thinkers consistently look for the role of systemic structures and forces in shaping behavior. Experts in systems family therapy, for example, help people interrupt their habitual blaming of self and others and begin to look for the systemic structures created within the family that shape individual actions such as how interactions between a mother and father may be a primary cause of a teenager’s problems, rather than just blaming the teen. By analogy, the problems of inequity are deeply embedded in larger social and economic systems. “Disparities (in income, health, employment, education) can’t be understood in isolation,” says powell. “They are embedded in systems in which there are many interactions and feedback loops.”[4]

But the converse, solely blaming the system, is equally counterproductive: “It’s not my fault; the problem is the system” leads to an attitude of victimization and obscures the simple fact that we are all creating the system through our day-to-day ways of thinking and acting. We find true systems understanding enables a particular kind of maturity. Individuals who can see systemic sources of problems can stop blaming themselves and start to look for ways to intervene in the system itself. We have had the privilege of working with many colleagues whose life circumstances would have easily supported victimization, self-criticism, anger and fatalism, yet developed very different attitudes — because they were able to see systemic structures at play. While perhaps not possible for everyone, one principal we know who grew up poor and black concluded that the attitude of victimization endemic in his family and many friends was ultimately a matter of choice and support.

I remember one day seeing clearly that the way I was being treated was not about me. It arose from a system of beliefs and habits that trapped perpetrators as well as victims. In that moment, I realized the system was outside of me and that I had a choice what beliefs I adopted. When I understood this, my circumstances did not change, but how I saw and reacted to them did change. I began a life-long inquiry into understanding the systems in which I found myself and learning how to conserve my sense of who I am at my essence and what is really important to me. Gradually, my anger dissipated and my insight grew.

Our present education system, while nominally committed to success for all students, actually embodies many success-to-the successful features that work against this aim, and changing these will be very difficult. The same remains largely true in the larger labor market it serves. Actions guided by ideas like those above will challenge a system structured to serve students inequitably, and those who have benefited from that system may resist change. But failing to do so over the past decades has made matters worse.

As noted by William H. Schmidt, co-author of Inequality for All, “The ultimate test of an educational system is whether it makes sure that every student, whatever their background, is exposed to the content they need to thrive in today’s society. U.S. schools are failing this most basic test, and in the process wasting the talents of millions of American children — children from all backgrounds. The reality is that, for most students, the education they receive is largely based on chance, making academic opportunities into a kind of lottery — one with profound consequences.”[5]

Today, the shortage of resources to support learning due to restrictions on public spending in many counties and localities, a condition that has changed little in the past decade, exacerbates the situation and makes reallocations within or between sectors politically difficult to manage.[6] In the face of such realities, we believe evidence of what can be achieved by dedicated leaders such as those described above can help shift the fatalism that subtly pervades the public discourse. Their work should be celebrated and utilized as inspiration to build a coalition of equity-based leadership.

As in all real systemic change, the journey requires patience and persistence guided by deep understanding. This is about all of us. The system works as it does because of how we work, and it will persist so long as we continue to adopt quick fixes and then return to business as usual. Leaders at all levels who achieve real progress embrace the entwined inner and outer journey that is imperative if we are to develop an education system that fully serves all students. Seeing the systemic sources of racism and inequity does not change them overnight, but denying them leaves the assumptions invisible and their power intact.

Notes

1. Richard Strong, Harvey F. Silver, and Amy Robinson, “Strengthening Student Engagement: What Do Students Want (and what really motivates them)?” Educational Leadership 53, no. 1 (September 1995): 8-12.

2. “Ten Steps to Equity in Education,” Policy Brief (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, January 2008), p.7.

3. john a. powell, Connie Cagampang Heller, and Fayza Bundalli, Systems Thinking and Race: Workshop Summary, Workshop Series on Racial Justice (The California Endowment, June 2011).

4. powell, Systems Thinking and Race: Workshop Summary, 2011.

5. William Schmidt (Michigan State University) and Curtis McKnight (University of Oklahoma), Inequality for All: The challenge of unequal opportunity in American schools (New York, New York: Teachers College Press, July 2012).

6. Ben Levin, “Approaches to Equity in Policy for Lifelong Learning,” paper commissioned by the Education and Training Policy Division, OECD, Equity in Education Thematic Review, August 2003.

Back to Top • Table of Contents • Download PDF

About the Authors

Mary Scheetz, Former Assistant Superintendent, Waters Foundation

Mary Scheetz has over 40 years experience as an innovative teacher, administrator, project director and consultant. From 2007 to 2013, Scheetz served as the Assistant Superintendent with the Ritenour School District in St. Louis and is currently a trainer and consultant working with the Waters Foundation Systems Thinking in Schools Team. She has presented systems thinking in schools work at numerous national and international conferences and facilitated related workshops. Mary’s belief is that all students are capable of the critical thinking levels that systems thinking tools produce, and that it is essential for schools to ensure that ALL students are ensured access to rigorous and relevant learning. As an assistant superintendent, she implemented multiple strategies for the integration of systems thinking in school improvement and classroom instruction. She developed the annual St. Louis Systems Thinking in Schools Institute, which involves participants from multiple school districts and universities in the region. Mary’s work is guided by the words of Marvin Weisbord, “If I had a crystal ball, I would not ask what’s wrong here and who’s to blame, but what’s possible here and who cares?”

–

Peter M. Senge Ph.D., Senior Lecturer, Sloan School of Management MIT, Founding Chair SoL (Society of Organizational Learning and the Education Partnership)

Peter M. Senge Ph.D., Senior Lecturer, Sloan School of Management MIT, Founding Chair SoL (Society of Organizational Learning and the Education Partnership), a global network of people and institutions working together for systemic change, and co-founder, The Academy for Systemic Change. Dr. Peter Senge’s work centers on promoting shared understanding of complex issues and shared leadership for healthier human systems. This involves major cross-sector projects focused on global food systems, climate change, regenerative economies and the future of education. Peter is the author of The Fifth Discipline and co-author of the three related field books to include Presence and The Necessary Revolution. The Fifth Discipline (over two million copies sold worldwide), was recognized by Harvard Business Review as “one of the seminal management books of the last 75 years,” and by the Financial Times as one of five “most important” management books. The Journal of Business Strategy named him one of the 24 people who had the greatest influence on business strategy in the 20th century.